Hazelrigg’s fight to grant astrology academic respectability

– September 7 – 13, 2007

It’s rather interesting reading John Hazelrigg’s preface to the Yearbook of the American Academy of Astrologians for 1918, on a number of levels.

One is to note how little has changed in the past 80-odd years when it comes to senior astrologers striving but struggling to gain a stronger footing of academic respectability for astrology and often feeling the need to rebuff attacks levelled at these efforts by uncharitable critics within the ranks of astrologers.

Another is the extravagantly intellectual (someone else felt ‘pompous’ even, but to my mind it is just in an old fashion of gentlemanly, albeit slightly carping, debate) tone and language of this New York astrologer’s verbal delivery in print. I would like to see a mainstream astrological publisher in the early 21st century let this kind of discourse past its editors, ever-conscious as they are of the need for mainstream market readability.

Since everything published in 1918 is safely out-of-copyright by a margin of over five years, it seems harmless to quote an extended section here:

“The water has gone once by the mill since the establishment of the AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ASTROLOGIANS, and though the gods grind slowly they have wrought finely and to felicitous purpose in the year that has passed. This statement is privileged in view of the encomiums that have come hitherward from various sources, commending the effort and the methods, and in other ways giving hearty emphasis to an endorsement of the undertaking.

“It is, however, an inexorable law of physics that one pole of a battery cannot be exercised without arousing opposite or adverse forces, and we are constrained to admit that the law in this instance has run true to form. Which leads us to remark that there is one sort of creature that is blind to any excellence that has the temerity to exist independently of his sanction, approval, or cooperation. He is not found in the ranks of the high-minded critic whose frankness and discrimination, though it combine a seeming harshness with the praise, must nevertheless stimulate and impel to further strivings.

“We are reminded in particular of one source whence a thriving petulancy of this nature periodically exudes, apparently through a constitutional belief that no good can come out of Nazareth so long as Nazareth is unwise enough to choose this particular astrological quarter as its Holy Place. Though it may not be whispered in Gath, nor proclaimed in Askelon, yet we have a lurking suspicion that this individual has either a kink in his superheated omniscience, or is affording asylum to an elongated specimen of the genus Toenia – though it would require a most ingenious bit of camouflage to disguise the fact that his superstructure is of too narrow a physical outline to permit even moderate freedom to the gymnastics of a truly husky cestoidean. Truly one knows not whether to go a-chiding at the childishness of it, or to gird oneself in sackcloth and ‘mourn before Abner’ for the pity of it. To say the least, however, such attitude so strangely persisted in can only beget distrust of its source, in that it reveals a spirit of silly prejudice or that of actual spitefulness, either of which is sufficient to make of any mother’s son a sort of corrugated nincompoop, and neither of which operates for the dignity or the upliftment of the Cause. The enemy within a camp can hardly claim a like justification for truculence as the open and avowed adversary outside the ramparts: the latter as a legitimate upholder of his hatreds and opinions may be pardoned his disgruntlement or his malice in a measure condoned – the other, alas! is merely a malcontent, and a very sorry specimen at that.

“The steadily progressive growth of Astrology in this country, in both a popular and academic sense, gives eminent satisfaction to those who have sincerely at heart the interest of the doctrine: not only by reason of this re-enforcement of adherents, but chiefly because of the calibre of intellect now being directed to its serious examination and its more than tentative acceptance. This valuable endorsement – or patronage, if you will – is not born of sudden impulse or of merely speculative curiosity, but proceeds from a gradual and thoughtful recognition of facts no longer regarded as being too fantastical for the intellectual gravities.

“One is so prone to imagine the votaries of the science as possessed of the uncogitative mind, or as including only the professional practitioner who may or who may not venture beyond the surface depths, that it gives pause to learn that its leaven has permeated the college faculty and laid metaphorical hold of the scholastic brain, as well as extending into the ranks of the law, of medicine, and of other technical avocations, and that one and all they are coming to realize that scientific punctilio owes a deference to the celestial tenets that can no longer be withheld.

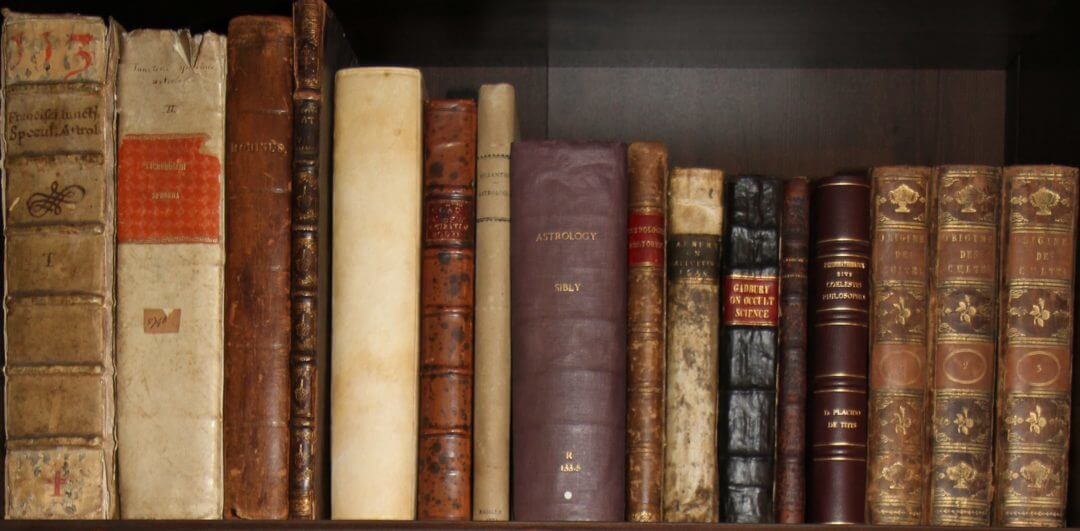

“And though these highly literate disciples are seldom or never heard of in the active circles, many of them represent a profundity of learning not heretofore looked for in the devotees of a science that should by all the laws of propriety attract only the most penetrative of intellects. The most acute astrological judgment it has been our good fortune to contact is that possessed by one of the foremost lawyers of Colorado, a practitioner in the Supreme Court of the United States, and who has found time and great personal satisfaction in collecting what is perhaps the most complete library of books and MSS. on the subject in the world. Another is a prominent physician of this city, who has developed a system of medical astrology that surpasses any such treatise now extant – and we have seen most if not all of them, good, bad, and indifferent. Unfortunately he does not yet deem it wise to permit his name to be associated with a work of this character, though he promises ultimately, at a time of greater expediency and of less hazard to professional considerations, to give to the world the systematized results and to take unto himself the onus probandi. And it is a part of the mission of this Academy to help remove the prejudices and to fabricate a spirit of opportunism that will serve to make potential just such accomplishment as this, which is already a silent actuality.”

Any guesses as to which Supreme Court lawyer and which prominent New York doctor he might be talking about? Tom, Kim, any ideas?

And as to the identity of the particular critic that Hazelrigg is trying to rebuff without naming him personally, anyone who can positively establish this with reference to other historical sources of the period deserves more than a good round of applause!

*****

– (In response to Tom Callanan’s suggestion of H. L. Cornell as a possible identity for the New York doctor:)

I had been thinking of Cornell too, but I don’t have any firm evidence to hand to establish that Cornell was ever based in New York.

I presume ‘this city’ refers to New York because the American Academy of Astrologians was based in New York, holding its regular meetings there, and also published its yearbooks from there (though as far as I’m aware no more than about two or possibly a few were ever published, starting in 1917).

There is an advertisement at the back of the 1918 yearbook for an early but quite lengthy work by Dr. George W. Carey called ‘The Biochemic System of Medicine’, but his address is clearly given as L.A., Cal., ruling him out.

The Astrologers’ Memorial site gives no location information for Cornell’s life other than his birth in PA.

The foreword to the Encyclopedia of Medical Astrology by Cornell is signed by him (in 1933) from Los Angeles, California, while the preface to the 1939 second edition is signed from the same location by his successor Henry J. Gordon, who was presumably too young in 1918 to have achieved the sophisticated model of medical astrology to which Hazelrigg alludes.

However, Cornell states in his introduction that it was in the fall of 1918 that he moved to Los Angeles with his family and gave up the practice of medicine after many years of work in the field, devoting his life to astrology and writing on it, and especially to compiling his encyclopedia. So he might have moved from New York in the very year that the 1918 yearbook was published.

Also I note that Cornell is listed as a member of the New York Psychical Research Society and an honorary profssor of Medical Astrology at the First national University of Naturopathy and Allied Sciences in Newark, New Jersey, both of which would suggest a strong east coast connection in his life.

I have a copy somewhere of Cornell’s earlier short book ‘Astrology and the Diagnosis of Disease’, published in 1918. The publication details therein could prove at least interesting, if a place is mentioned. I’ll see if I can find it and edit this post if it shows up anything interesting!

PS: The first edition of the Encyclopaedia of Medical Astrology was published in 1933 when Cornell was still alive; the second edition published in 1939 with the added foreword by Henry Gordon was posthumous. The bindings of the two editions are apparently identical externally, and the 1933 date is retained internally, leading many a bookseller to mis-sell a second as a first by not bothering to read on as far as Gordon’s note. I bought a second mis-sold as a first myself, but since it looks the same on the outside and since the bookseller was in Australia and these volumes weigh a lot I didn’t think it was worth sending it back at Swedish international post rates….

*****

– (In response to Ed Jacobsen, Jr.’s recollection that Hazelrigg was a poet at university and then became a stage actor in New York:)

Going back to Hazelrigg, I can see in the light of your reports on his love for poetry and training as an actor that this was not necessarily a typical verbal diatribe even in 1918, and that it had his personal stamp very much written upon it. One of someone else’s first thoughts was that he was trying so desperately hard to confer a veneer of intellectual respectability to his profession and the work of the American Academy of Astrologians in particular that he massively overdid his verbal style and ended up sounding as though he was trying to fake intellectual credentials he probably did not have in such great measure. I have the feeling that he must have been quite intelligent to come up with such a text as this, hideously and tortuously convoluted though it sounds, but still it may be true that he was trying to exaggerate his own intellect in order to adopt an apparent position of intellectual superiority unvanquishable by the detractors of his efforts. This in itself, I believe, was nothing new for a writing astrologer, as I think back to Renaissance-era texts in which authors such as Partridge invested a great deal of verbal energy in trying to sell the intellectual strengths of their own particular treatises to their readerships and the public at large, but still it arguably harks back to a certain inferiority complex in the astrological profession at large carried down through the centuries….

Leave a Reply